Short-Sighted Politics With Long-Term Consequences: Black Activism, The 1960S, And The Creation Of The Anti-Riot Act

by Andrew Allen, Esq.

The Anti-Riot Act of 1968 is a dangerous law and, for many reasons, is unconstitutional.

After lying dormant for decades, 18 U.S.C. §2101 and §2102 were resurrected by the Justice Department in 2018 to prosecute four young men in California and four other young men in Virginia. The California defendants had scuffled with Antifa members at a Trump rally in Berkeley, California, in April of 2017. The Virginia defendants had attended the Unite-The-Right rally in Charlottesville. Federal jurisdiction was asserted in California because the Justice Department claims one of the defendants used a credit card to rent a van used to drive to the rally.

This article focuses on the California case and legislative history of the Anti-Riot Act as instructive of the respect Congress gives to the First Amendment and the deference the Federal Courts give to Congress.

The legal issue is the important but esoteric concept of the standard of review a court should apply when considering the constitutionality of a law. Standards range from the Rational Basis standard, which gives maximum legal deference to Congress, to Strict Scrutiny, the most rigorous form of judicial review.

It is hornbook law that criminal legislation directed at either a suspect class of defendants based on race or at First Amendment rights is subject to a strict scrutiny review by the courts.

In amicus curia briefs presented in two federal courts of appeal, including the Federal Ninth Circuit, the Free Expression Foundation (FEF) argued that the Act should be subject to strict scrutiny as a law directed at Black political organizers and fundamental First Amendment rights. Yet instead of cleanly striking down the Act, the Ninth Circuit Panel “saved” the Act by severing various parts it found unconstitutional, concluding that “Congress would prefer severance over complete invalidation.”

Because of the immense importance the Ninth Circuit Court Panel gave to “the preference of Congress,” and because of the applicability of strict scrutiny review, FEF drew upon the extensive legislative history of the Act.

We leave it to the reader to judge the “preference of Congress” when it drafted the Act.

Legislative History

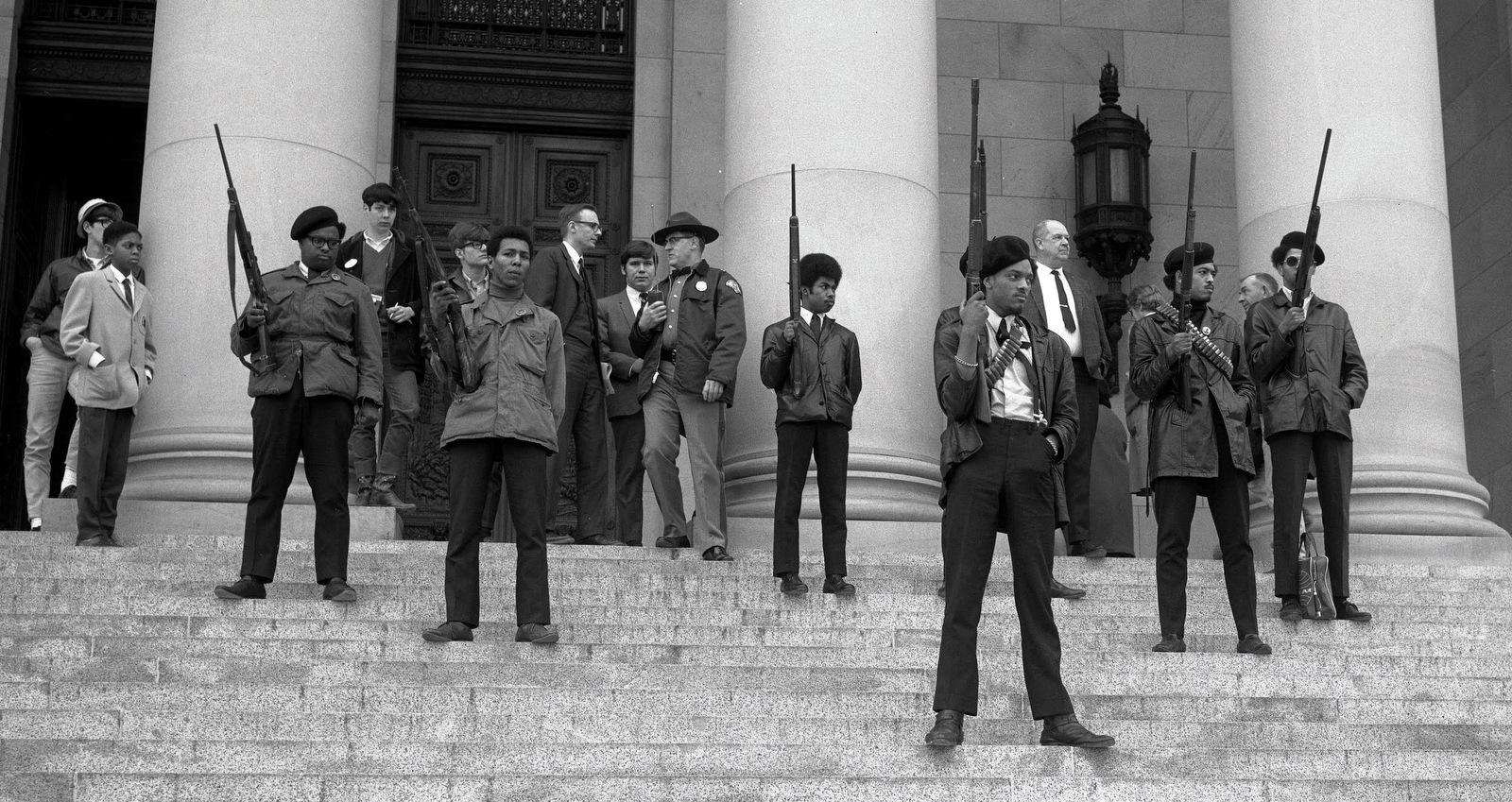

The Anti-Riot Act was Congress’ response to the race riots which blew up in American inner-cities in the 1960s. It was passed as an attachment to the Civil Rights Act of 1968 as smoke from the Washington D.C. riot was still in the air and troops with bayonet-affixed rifles were still surrounding the Capitol building.

From 1966 onward, dozens of congressmen stepped forward to present laws to deal with Black rioting. The most draconian of these was HR 421, introduced by Representative William Cramer (R — Florida). The record shows the legislation was directed against the First Amendment rights of Black political organizers who were accused of “stirring up” otherwise peaceful Black neighborhoods.

The focus on Black protesters is clear. Of the 138 riots reviewed by Congress, all involved Black rioters except for two anti-war demonstrations. Graphs prepared by Congressional staff carefully listed the percentage of Blacks in each city where riots occurred. The specific targets of the law were radical Black political activists of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). SNCC, or its members, were mentioned more than 120 times during the Senate hearings. Communists were mentioned 29 times and the Black Panthers four times. No other groups were given more than a brief mention.

Representative Cramer explained his reasons for the bill:

“One cannot overlook the fact, either that in many cities which have fallen victim to these riots this summer and in summers past outside instigators are in some way connected with them. The causal connection defies coincidence. For example, the presence of a free-lance insurrectionist precedes many of the outbreaks. He works up his audiences to a fever pitch. He tells them they are downtrodden, that ‘black power’ is their salvation, that the Negroes must take the law into their own hands, that they must ‘kill Whitey,’ and that they must ‘burn, baby, burn.’… He exhorts his audiences to say, ‘To hell with the draft.’ ‘Hell no, I won’t go’ is the cheer he leads, and listeners, caught up in a frenzy of emotion, repeat after him, ‘Hell no, I won’t go.’ “He then usually leaves that jurisdiction. In his wake are thousands of Negroes whose blood is simmering waiting for the instance certain to occur in any large city when a felon is arrested or shot.”

The Senate version of HR 421 was introduced by pro-segregationist Senator Strom Thurmond (R – South Carolina). A staunch opponent of civil rights legislation in the 1950s and 1960s, Thurmond conducted the longest speaking filibuster up until that time (24 hours and 18 minutes) in opposition to the Civil Rights Act of 1957.

Senator John McClellan (D — Arkansas) entered the following into the record, echoing Representative Cramer:

“Like the poor, slums and rats have always been with us. Only the devastating riots-and the professional agitators who prepare the tinder to await a spark and fan the flames-are significantly new.”

The proponents of HR 421 saw no rational basis for the riots that broke out in urban concentrations of African-Americans because, as a letter from a Federal judge stated:

“As you know, the White people of the South, having lived with the Negro for generations, have developed a real fondness and spirit of friendship for him. This, I think, is true with a majority of both races.”

Representative William G. Bray (R — Indiana), for example, declared:

“We are told these riots – and crime in general – are due to poverty and social deprivation. This is not so.”

He went on to describe the activities of SNCC:

“The banners of what has the appearance of a deliberate reign of terror are borne by a group of malcontents and would-be revolutionaries whose potential for danger goes far beyond their numerical strength. They preach and promote a nightmarish, nihilistic tide of thought that calls for either immediate change or immediate destruction. They, and their kind, have arisen under the disastrous and ill-advised doctrine of permissiveness…”

HR 421 was not meant to duplicate the already comprehensive set of laws against public disturbances. Instead, it was a “get tough law” directed at SNCC and the Black Panther Party.

Representative Albert Watson (R — South Carolina) declared:

“The only way to curtail crime in this country is by a get-tough policy. As I said before, this bill will not necessarily eliminate violent civil disturbance, but its passage is a beginning.”

SNCC organizers were held in contempt, and their words and actions were seen as dangerous per se. Thus, HR 421 was drafted as if the political discourse and organizational activities of SNCC organizers were no more than an organized criminal enterprise.

Representative Cramer explained:

“The language of my anti-riot bill follows closely the language adopted by the Congress in enacting the 1961 anti-racketeering act which I cosponsored and which made it a Federal offense to travel in or use a facility of interstate commerce with the intent of aiding organized criminal activities.”

A Crime of Intent

Congress cast a wide net with the passage of the Anti-Riot Act, creating an inchoate crime — a crime of holding an intent to do a future act. Punishment was set at up to five years in prison. In addition, federal jurisdiction attached any time a citizen crossed a state line or used a “facility of interstate commerce” while holding an intention to do any one of nine acts that might lead to a public disturbance.

The term “facility of interstate commerce” includes the use of a telephone, radio, telegraph, mail, a cell phone, the internet, a credit card, or texting; any such use can establish Federal jurisdiction. It would make no difference if the use was in your home or from your child’s backpack. In all such cases, the Federal government could step in with criminal charges.

Performing an “overt act” is required for the completion of the crime. But the legal term “overt act” has been especially construed by the Federal courts just to preserve the Act. In California, for example, texting friends to meet for lunch is an “overt act,” as listed by prosecutors.

The key get-tough provision of the Act is the targeting of mere intent. No actual riot or violence need occur. Instead, as California District Court Judge Cormac Carney correctly pointed out, the Act improperly focuses on pre-riot communications and actions. But, of course, that is precisely what Representative Cramer intended.

The Dismal History of the Anti-Riot Act

In passing the Anti-Riot Act, Congress followed a trend often displayed in moments of national crisis. At such times laws are passed without consideration of long-term effects and inconsistent with traditional American values and First Amendment rights.

During World War I, Congress passed “The Espionage Act of May 16, 1918” (repealed 1921), which read in part:

“Whoever shall willfully utter, print, write, or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government in the United States shall be punished by imprisonment for not more than twenty years.”

In 1940 Congress passed the Smith Act, portions of which make it a Federal offense to advocate the overthrow of the government by force or violence.

Despite its intended use against SNCC, the Act was quickly turned upon opponents of the Vietnam War. The first prosecution under the Act was of the “Chicago 8.” After that, the Act was used to subpoena members of the Black Panther Party, to prosecute the Vietnam Veterans Against the War (also known as the Gainesville 8); to justify a raid by the Joint Terrorism Task Force on a Leninist collective; to seize the computer of a Palestinian sympathizer; and to spy on the late John Lennon. However, after 1992 the Act was not invoked for another 25 years.

Judicial Deference to Congress

In many areas, there are solid reasons for the courts to defer to Congress. Still, FEF advocates that the Federal courts be watchful guardians of our Constitutional liberties with the First Amendment.

Yet, so far, the Act has escaped strict scrutiny. The Ninth Circuit Panel ignored the words of the Act’s proponents, the language of HR 421, and the Act’s history of political prosecutions. Rather than strike down a dangerous and abhorrent law, the Panel accepted at face value the government’s erroneous claim that the Act was only directed at interstate instigation of violence, and the Panel only pecked away at a few obvious unconstitutional provisions.

The Ninth Circuit has kowtowed to the supposed “preference of Congress” regarding the criminalization of First Amendment activities. It is highly unlikely that Congress would pass such a law today. In this case, severability is merely a doctrinaire excuse by a weak court determined to save as much of a bad law as possible.

This is not to say that the Ninth Circuit Panel did not engage in highfalutin rhetoric:

“We recognize that the freedoms to speak and assemble which are enshrined in the First Amendment are of the utmost importance in maintaining a truly free society.”

Yet they then immediately endorsed criminalization of a wide range of acts related to assembly, free speech, and the press:

“Nevertheless, it would be cavalier to assert that the government and its citizens cannot act, but must sit quietly and wait until they are actually physically injured or have had their property destroyed.”

Representative Cramer would have approved.

As Judge Carmack Carney noted, there is no need for the Anti-Riot Act. There are already more than enough state and federal laws dealing with any and all actual or threatened violence. The Act adds nothing to the government’s arsenal of laws except the creation of a thought crime and the expansion of Federal jurisdiction over minor scuffles at political rallies. History has taught us that any political thought crime trials (such as prosecutions under the Act) will inevitably degenerate into conspiracy trials. The targets will always be political outcasts, and the government’s case will be glued together by comments trolled from the internet or an occasional “confession” extracted from an alleged “co-conspirator.”

As other courts have explained, rioting, in history and by nature, almost invariably occurs as an expression of political, social, or economic reactions, if not ideas. Thus, the rioting assemblage usually protests the policies of a government, an employer, some other institution, or the social fabric in general.

Our nation’s heroic founders risked their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor for freedom. Yet, they were well aware that they were no more than criminals in the eyes of the British insurrectionists. The speeches and writings of the latter left thousands of citizens with blood simmering for Independence.

Under British oppression, the rioters became revolutionaries. Upon Independence, the revolutionaries shared the common understanding that freedom is dangerous to vested powers and that vested powers will attempt to stifle freedom. There was a widespread feeling among the revolutionaries that the tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants. With the full experience of civil strife and bloody war, the revolutionaries put into the First Amendment protections of the revolutionary freedoms of speech, assembly, and the press.

And there you have it. The First Amendment is not about etiquette at the library. It is about protecting rights that can be revolutionary, contentious, and sometimes dangerous but are necessary for a free society. Unfortunately, when the Federal courts clucked over stopping the possibility of a broken window or fisticuffs between a few hotheads, they lost sight of the profound revolutionary reason for First Amendment rights. Instead, they broke faith with the Americans whose blood was spilled on the cobblestones of Boston, with our revolutionary Founders who drafted the First Amendment, and with the Black students and organizers who were the initial targets of the Anti-Riot Act.

The Anti-Riot Act was a legal tragedy by any measure. The political expediency of the 1960s was traded for the long-term protection of our First Amendment rights, a devil’s bargain for which we are paying dearly in these turbulent times.

The defendants in the Ninth Circuit case will be filing a petition for review by the Supreme Court of that dangerous and error-filled decision. FEF as amicus will be supporting that petition.

Andrew Allen is a San Francisco-based attorney who practices civil rights and constitutional law. He’s been a valued member of the FEF team for most of its history.

If you found this information useful, please consider making a small tax-deductible donation to the FEF. Every dollar counts in our fight to keep Free Expression free. Click the DONATE button at the top right corner of this page, and thank you!

*** IMPORTANT DISCLAIMER***

Information herein and throughout this website is for educational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice directed towards individuals, groups, or organizations.

FEF does maintain relationships with lawyers, law firms, and other experts throughout the United States and can help direct people towards such resources and, to an extent, serve in an advisory capacity. But the FEF is not, in any way, a law firm or legal partnership.

The FEF recommends that legal advice should always be obtained by a qualified attorney licensed to practice law in the relevant jurisdiction.