FEF Denounces UCLA Decision To Bar Michael Miselis From Completing His Ph.D In Aerospace Engineering

Michael Miselis, one of the defendants in the Charlottesville Rise Above Movement prosecution, could make a strong case that he has been the victim of a flagrant miscarriage of justice, and one whose pernicious consequences roll on and on.

Much of Miselis’s ordeal has arisen because of the plea agreement he signed. No fair-minded person, however, who is familiar with the Heaphy Report about the Charlottesville Rally and knew the nature of the charges and ambiguous evidence against Miselis, his harsh conditions while incarcerated, and his dismal prospects for a fair trial would give much weight or credence to that plea agreement. In the agreement, Miselis admitted to participating in violence during the Rally. But the reality is that amid a general melee he was involved in a few minor scuffles with counter-protestors who were at least as aggressive as he was but were never charged with any crimes. These scuffles easily could have been avoided if the Charlottesville police had done their job, as the Heaphy Report makes clear. Miselis did not seriously injure anyone, but nonetheless was sentenced to 26 months in prison, which he has now served.

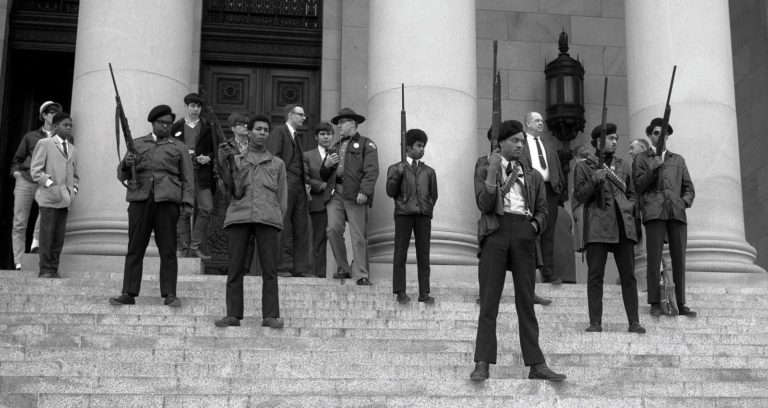

As an essential condition of his plea agreement, Miselis reserved the right to challenge the First Amendment constitutionality of the Anti-Riot Act statute under which he was convicted. That statute, hastily enacted in the context of the civil unrest of the 1960s, had rarely been used before the government dusted it off and invoked it against the Charlottesville pro-monument demonstrators. Its constitutional flaws are many and serious; it was in fact struck down on First Amendment grounds by Judge Cormac Carney in the California RAM prosecutions. Accordingly, Miselis’s hope to overturn his conviction by the condition in the plea agreement allowing him to challenge the statute was well-founded.

That hope proved a mirage. The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals in Miselis’s case severed some of the statute’s manifestly unconstitutional language, judicially construed other language in defiance of its apparent meaning, applied the now judicially truncated and revised statute to Miselis’ plea agreement, and by this convoluted path upheld his conviction. In essence, Miselis was induced to enter into the plea agreement by the promise he could challenge the constitutionality of the Anti-Riot Act, but the plea agreement itself was then used to defeat his constitutional challenge.

Unfortunately, the Fourth Circuit’s logical wizardry was not the last instance in which Miselis’ plea agreement was unfairly used against him. Before the Charlottesville events, Miselis had been a graduate student in aerospace engineering at UCLA, about a year from completing his Ph. D. After he had completed his prison sentence, he was initially – for about three months – allowed to resume his studies. But in late May 2021, he was brought before the UCLA Student Conduct Committee to face charges he was a safety threat to persons on the UCLA campus and should therefore be dismissed from the university. About a month later, the committee issued its report recommending dismissal.

The committee’s rationale is as illogical as the Fourth Circuit’s had been. The committee, relying on Miselis’s admissions in his plea agreement, concluded he is a safety threat even though: there had been no problems whatever during the three months he had been allowed to resume his doctoral studies; his remaining months of study could easily be conducted remotely, a practice the university had perfected during the Covid lockdown; he lives 300 miles from the UCLA campus and agreed he would never return to it; and his probation requirements, with which he has scrupulously complied, barred him from leaving the federal Eastern District of California, whose closest boundary lies 100 miles from the UCLA campus. The committee’s conclusion that Miselis is a safety threat is bizarrely irrational.

There is also the question of whether the university singled out Miselis for such draconian treatment. A basic internet search supports an affirmative answer, for it reveals that UCLA:

- has welcomed into the university many persons with criminal records, including persons with violent convictions such as murder and attempted murder and gang affiliations;

- has welcomed many other students who had been arrested for activities relating to protests, including violence;

- has proclaimed in various mission statements the desire to remain accessible to those formerly convicted;

- has accepted state funding earmarked for promoting formerly incarcerated students;

- has approved student political organizations presently engaged in criminal behavior, including “The Revolutionary Club,” whose parent group had been involved in violence at several events including the Charlottesville rally; and

- has staff and students signatory to criminal and /or terrorist groups such as Antifa.

The Fourth Circuit’s labyrinthine opinion and the Student Conduct Committee’s surreal report raise a strong suspicion that these decisions were motivated by hostility to Miselis’s protected First Amendment activities. All Americans deserve more principled and transparent decisions than these.

FEF has offered its resources to Mr. Miselis for possible redress in federal court.